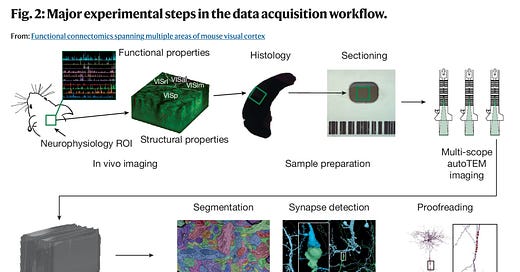

1: A bunch of articles were formally published this past month using the MICrONS data set. There are two parts to this. First, it has calcium imaging of around 75,000 neurons in the primary visual cortex and higher visual areas from an awake mouse that was viewing natural and synthetic stimuli. Second, this is co-registered with an electron microscopy-based connectomics data set containing more than 200,000 cells and 500 million synapses. That’s a lot of synapses!

One of the studies that uses this data set starts with the functional recordings and trains a foundation model on it. With this model, they had a vector embedding for each neuron that describes its input–output function, where the input is the visual stimulus shown and the output is how the neuron responds to that stimulus (measured via calcium imaging). They found that these vector embeddings could predict structural properties of the neurons, like what visual area it belongs to and what morphological cell type it is. This is an interesting method but perhaps not too transformative of a finding, as we already know that electrophysiological signatures can differ between regions and cell types.

What I would most like to see (and I couldn’t find on a preliminary search) is a study attempting to use this data set to do the reverse: using the structure and our pre-existing knowledge of neuroscience, attempt to predict the calcium imaging results. Even if this is not yet possible with this data set and our existing knowledge of neuroscience to constrain the model, that would be interesting to know. This data set could potentially be used as a benchmark to measure the extent to which our capacity to predict function from structure might increase (or not) in the coming years.

2: New study finds that synapsin proteins undergo liquid-liquid phase separation and create condensates that recruit and polymerize the cytoskeletal protein actin. Actin then creates the stable molecular networks that maintain synaptic architecture. To me this is another example of the spatial correlation of biomolecules at synapses, and how no single molecule type is an island.

3: New method to measure brain-wide synaptic protein turnover. Finds that most synaptic proteins, like PSD-95 and GluA2, have average lifetimes in the range of 3-18 days.

4: Faster BCIs that can map brain signals during silently attempted speech to create synthetic speech within 3 seconds.

5: An article claims that compared to chimpanzees and rhesus macaques, humans have especially strong connectivity in certain white matter tracts in the temporal and parietal regions. This challenges the idea that the prefrontal cortex is the main site of human brain uniqueness. It makes sense to me because these white matter tracts are often associated with language processing and social cognition.

6: CSF proteomics study on n = 3397 participants finds that synaptic proteins are the strongest predictors of cognitive impairment, independently of Aβ and tau. The ratio of two proteins, YWHAG to NPTX2, predicted subsequent conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia, even adjusting for APOE, age, p-tau/Aβ ratio, and other known risk factors.

7: Thomas Reilly has an interesting article touching on the recent natural experiments suggesting that varicella zoster vaccination might prevent dementia. Based on my priors seeing promising things fail in this space, I would still be willing to bet that a large RCT for shingles vaccination for dementia prevention would not have any effect. Perhaps at 8 to 2 odds. That said, such a trial should still proceed if it is one of the best prospects available. And I myself would love to get a varicella zoster vaccine at an age younger than 50, and maybe a booster shot later as well. It seems to have low downside and high upside, even if only in mitigating the risk of shingles. I wish I had more freedom to access this — or maybe I do and I don’t even realize it.

8: fMRI study finds that methylphenidate increases dwell time in the frontal parietal network, which is a resting state network that has been previously associated with coordinating behavior in a rapid and flexible manner.

9: Study finds that valbenazine becomes more effective over the course of one year when used for tardive dyskinesia in people >= 65 yo. The mean change from baseline AIMS was -4.5 at week 8 of treatment and -8.8 at week 48.

10: Study finds that there is no increase of Alzheimer disease neuropathological changes (ADNC) in people with schizophrenia and long-term use of antipsychotic/neuroleptic medication. This leaves open the question of why this population of patients is more likely to get dementia. The most likely explanation to me is that schizophrenia is associated with cerebral small vessel disease, likely due to metabolic changes. This would be a mechanistically “boring” explanation, which is one reason it might be under-appreciated. However, there also could be some other type of neuropathology in people with schizophrenia that is associated with an increased risk of dementia that is not yet known.

11: You have probably already heard of this, but the huge news in obesity medicine this month is that Eli Lilly’s oral GLP-1 medicine, orforglipron, was found to be as effective as injectable GLP-1s. Beyond the people who simply will not use needles, my guess is that this will change the cost-benefit calculation for many fencesitters when it is widely available (which I’d guess will probably take a few years).

12: Study finds that that people with intuitive eating styles (vs emotional) are more likely to have significant (>10% or 15%) weight loss with semaglutide. Relatively small sample size, difference-in-differences effect (which are always more tenuous), so my guess is that there is a good chance it would not replicate, but might be of interest.

13: Biomolecular archaeology identifies the binding of some medieval manuscripts as being made of seal skin. With proteomics they were able to determine that it came from a seal, and with ancient DNA analysis they were able to determine that it came a Harbor seal.

14: Historian argues that the first known soccer (football) field was in Scotland and that this is where the game originated. Total Scottish cultural victory.

15: A study uses inference based on ancient DNA to suggest that around 1.5 million years ago, the ancestors of modern humans split into two distinct populations, labeled as populations A and B in the paper. These two populations then remained separate for over a million years. Population A, which eventually contributes ~80% of modern human ancestry, went through a severe bottleneck immediately after the split, meaning its population size decreased dramatically. Not being an expert in this field at all, I wonder if this could correspond to a migration event (notably, it is thought that the earliest hominins first migrated out of Africa into Asia around 2 million years ago).

Then around 300,000 years ago, these two long-separated populations came back together and mixed. They found evidence of selection against DNA from population B after the admixture, suggesting it may have been somewhat deleterious when mixed with the A background. However, they found that certain gene categories showed enrichment of population B ancestry, particularly those associated with neuronal development and processing.

16: Skepticism about contemporary polygenic scores in psychiatry, embryo selection, and social science.

17: Tragic news as John Beaulaurier, a brilliant, extremely kind scientist who was in the genomics program with me at Mount Sinai, has died of cancer at 41.

18: Large biometric device study (4,084,354 person-nights) finds that late evening exercise is associated with worse sleep:

Exercising at least 4-6 hours before sleep seems to be the safe zone, depending on the intensity of the exercise.

I have a hypothesis that the same phenomenon is true of intellectual work and that it is helpful for sleep quality to stop this for some period of time (potentially hours) before sleep. It’s also likely true that people vary in how sensitive they are to this phenomenon.

19: After reading this article by historian Samuel Biagetti, “The return of the eunuch,” I found an interesting forum thread on asexuality.org from 2004 about the topic. I wonder what happened to “CyberThalamus”, who reportedly became a voluntary eunuch, got a 95th percentile on the MCAT, wrote “I've reafirmed my commitment to science and am going to study neuroscience. The things I want to study and help with will change everything for everyone,” and recommended that someone else should “Wait for the singularity.” One thing we clearly agree upon is that the thalamus is a critical brain region.

20: A review of methods for perfusion fixation in laboratory animals. One takeaway is that the methods different labs use for perfusion fixation are pretty diverse. It seems there is still room to figure out what the most effective methods are even in this controlled setting.

21: Podcast with Mark Woodward on his new company Wake Bio, which has the goal of developing new cryoprotectants and enabling provably reversible cryopreservation. They are staring with zebrafish as their first test organism, and using AI to explore the chemical space. Personally, I expect his timelines for when provably reversible whole body cryopreservation will be developed are quite unlikely, but I respect his motivations and wish him the best of luck.

22: AMA from a few months ago with Joe Strout, a “connectomics engineer,” on the Bobiverse subreddit. He predicts that a mouse brain connectome will be mapped in 5 years. Someone also asked him if he’d want to go through with the process of preservation followed by eventual mind uploading himself. His answer: “Absolutely! My own TODO list is probably about two centuries long, and seems to keep getting longer.”

23: The neuroscientist Dean Burnett has written a short critique of cryonics. Here are my responses to his points.

Cryogenically freezing someone is rarely, if ever, permitted before that person has died. Why? Because freezing a living body is inherently a lethal process and, even if they’re okay with it, it’s illegal to kill a person.

Preservation is never allowed before a person has legally died. So this is technically true but it is a strange way of putting it to say that it is “rarely, if ever, permitted.” The link doesn’t clarify anything, although it happens to be a great article.

More importantly, no sufficiently complex living organism is ever fully inert. It’s always biologically active, being sustained by innumerable biochemical processes. Freezing shuts these down. Turning them back on again isn’t like flicking a switch on a machine, but more like trying to unscramble an egg. While not impossible with sufficiently advanced technology, it’s certainly not easy.

This depends on how one defines life. Not only do we not have a good definition of death, but we also don’t have a good definition of life. If one defines life as requiring ongoing biochemical processes, then this is tautological. If one does not define life in this way, then it seems to me that nematodes and other small organisms disprove this claim, as they can effectively be made fully inert (stopping biological time) via cryopreservation and then revived via rewarming. Perhaps he would say that those organisms are not “complex” but I think attempting to argue such a claim would be even more quixotic. Let’s not bring Aristotle’s ladder of life into this.

It is also clearly not true that reversing preservation is necessarily “like trying to unscramble an egg.” For example, there are plenty of people walking around today born via IVF who were previously preserved as embryos.

The internal structure of a neuron is also very intricate and far more vulnerable to chemical and physical damage. Also, while other tissues may be able to regenerate or repair damage caused by a less-than-perfect cryogenic process, neurons struggle to do this. So, the brain is both more vulnerable to harm from the cryogenic process and less able to recover from it.

And this is key. It’s not just the presence and number of neurons that support our minds and consciousness, but the exquisitely precise and sophisticated way in which they’re arranged and linked. The typical brain contains trillions of spindly microscopic neuronal connections, which are how our memories and identities are stored. Such fundamental connections would be very easily wrecked by the freezing process.

Even if future medicine could rebuild and restore these connections, how would a future neurologist know what connections go where? Unless you have a full molecular-level brain scan before you’re frozen, and that scan is stored with your head or body, trying to rebuild neuronal memories would be like trying to rewrite a burned book by studying the ashes.

His main point here is one I absolutely agree with. It’s why I am focused on structural brain preservation.

Basically, however it’s set up or applied, every modern manifestation of cryonics relies on one vital resource: optimism. And while there’s nothing wrong with that per se, you’d hope people would think twice before gambling their lives on what is currently a very unlikely outcome.

On what is he basing his claim of the low current likelihood of success? I would like to see some kind of analysis regarding that. It seems to me that the probability of success is highly uncertain and depends on all sorts of contextual factors.

Regarding whether people are “gambling their lives,” there are a couple ways to think about it.

First is the question of whether to pursue preservation at all. This is not gambling one’s life. There is no other game in town. Either people pursue preservation, which has the possibility of information-theoretic death, or they don’t, in which case they have guaranteed information-theoretic death. Perhaps one could say it would be gambling one’s life to not do it, but I think that would be a manipulative and misleading framing, and anyway it seems contrary to Burnett’s overall stance.

He could have easily argued instead that people are gambling their money — that is, unless they go with a free option (in which case they would actually be saving money compared to a conventional funeral). This is clearly true. But people do this all the time, spending their money on things with uncertain success, whether that is related to health, entertainment, or anything else.

Second, one could imagine him referring to which preservation option to choose. I doubt this is what he means. But if it is what he means, then I would wholeheartedly agree. I think people very much should think twice about which preservation option to go with. And three times, four times, etc.

We are "gambling our lives"? That's hilarious. I'm giving up the absolute certainty of death for a chance at life. What was I thinking?

Regarding #23: This is why I'm so glad we did our survey, so we can go to people like Dean Burnett and say "0%, really? The field gives it about 40% buddy".