People who are interested in cryonics have a far and away favorite conversation topic, which is why other people aren't interested in pursuing cryonics. There have probably been hundreds of proposed theories and associated remedies over the years.

These theories rise and fall in popularity. For years one of the most popular was the Celebrity Preservation Hypothesis. If we could just get one celebrity to choose to be cryopreserved, then finally people would care and start signing up in droves. Just one.

Well, it happened. In 2002, Ted Williams was cryopreserved at Alcor. It... didn't go exactly as planned. There was an outpouring of negative press. Alcor was nearly put under the control of the Arizona funeral board, whose director told the NYT “[t]hese companies need to be regulated or deregulated out of business." They were ultimately able to successfully lobby to prevent this. Cryonics Institute (not even involved!) underwent hostile regulation, receiving a "Cease and Desist" order for 6 months before being legally re-classified as a cemetery. Of course, Alcor made mistakes with this case, which is a confound. But cryonicists don't really suggest anymore that all we need is one celebrity. Turns out that the whole celebrity thing might have been a bit misguided.

From a sociological perspective, I love the idea of testing these theories of change. We get actionable data instead of pontificating all day. So I've been excited that in the past few years, a few theories of change that have been discussed for decades are finally being put to the test.

The first is public relations. Do people even know about the idea behind preservation and how they could personally use it? Nearly every model of consumer decision-making has this at its core. Tomorrow Bio, a new preservation organization in Europe, has taken this to heart. They have hired marketers and have been working hard to spread the idea of preservation. So for anyone who thought that this was the key ingredient missing -- as many have suggested over the years -- this hypothesis is currently being tested.1

The second is free preservation. Surely the problem is cost? I myself am somewhat partial to this explanation. Now three organizations are offering free preservation -- Cryonics Germany, the Brain Archive at the University Hospital Erlangen, and Oregon Brain Preservation (where I work as a researcher). It remains to be seen the extent to which people will be interested in this.

The third is hardcore reversible cryopreservation research. These suggestions tend to go along the lines of "if we could bring a mouse (or person!) back to life, then finally people will start paying attention." Robert Prehoda published a whole book about this way back in 1969.

Last week a new research organization, Cradle, announced that they are entering the space with the explicit goal of performing R&D on reversible cryopreservation procedures. They are very well-funded with $48 million and staffed with many well-educated scientists. This seems to be exactly the type of reversible cryopreservation research organization that people have been asking for.

Are any of these theories of change going to work? At least as measured by getting many more people to sign up for preservation, my personal guess is that most likely no, none of these approaches will be very successful. For the past several decades, the number of people who have been preserved has doubled around every 8 years. Exponential trends like this have a way of continuing on. This trend will probably continue rather than accelerate. But I would love to be proven wrong.

To be clear, I also buy Brian Wowk's argument that using sign ups as the main metric of success is a terrible idea. At least from an R&D perspective, the main goal should be to figure out how to preserve people so that they have as good of a chance as possible of living on in the future, and implement those procedures for those who desire it. The extent to which the public is interested is only a crude proxy -- if there is even an association at all -- for the actual critical question of how likely the procedure is to technically work. But still, I find it quite interesting that all three of these hypotheses are now being tested, and I'm curious to see how they pan out in the next 5-10 years.

In this post, I want to hone in more on the new organization Cradle. What exactly are they planning on doing? I think they have given enough public clues that we can try to piece the picture together.

Memory in brain slices

So far, the research they have reported has been on the electrophysiology of rodent brain slices that have been cryopreserved and rewarmed. Certainly interesting results. It reminds me of the work by Anatoly Mokrushin, who has been publishing numerous studies on the electrophysiology of brain slices after cryopreservation (e.g. see here, here, or here). And also of previous research on the electrophysiology of cryopreserved mollusks.

Here's co-founder Laura Deming on what they are planning next:

So the next milestone we're aiming to hit is to show that you can preserve memory in a slice of brain tissue that has been cryopreserved and rewarmed.

I'm not exactly sure how they are going to operationalize the measure of memory preservation. My best guess is that they will measure whether long-term potentiation (LTP) can be preserved in brain slices.

LTP is a durable strengthening of synapses between neurons that is widely used as an in vitro model of learning and memory formation. It involves an increase in the strength of the signal transmitted between neurons or neuronal populations when they are simultaneously stimulated.

However, while LTP is a well-established model for studying memory at the cellular and tissue level, the relationship between LTP and complex memory functions in the intact brain is still an area of active research.

Moreover, as Brian Wowk pointed out, preservation of LTP has already been reported in cryopreserved and rewarming rodent brain slices in a 2012 paper. Part of the reason people are skeptical about this research translating to human cryopreservation is that brain slices are much easier to cryopreserve than a whole brain. You don't have to deal with the blood-brain barrier and, because slices are so much thinner, the cooling and rewarming rates can be much faster, which helps prevent ice damage. So it is a little bit unclear how much people will care if Cradle is also able to show LTP preservation after cryopreservation and rewarming of brain slices.

To be absolutely clear, I’m not saying that people shouldn’t care about this result. I think they absolutely should! This is an important result underlying the basis of brain preservation. And I think replicating it with more reproducible methods would be a very important contribution. But as far as I am concerned, people should already care, and they don’t, so it’s not clear that this is going to get more people interested in the field.

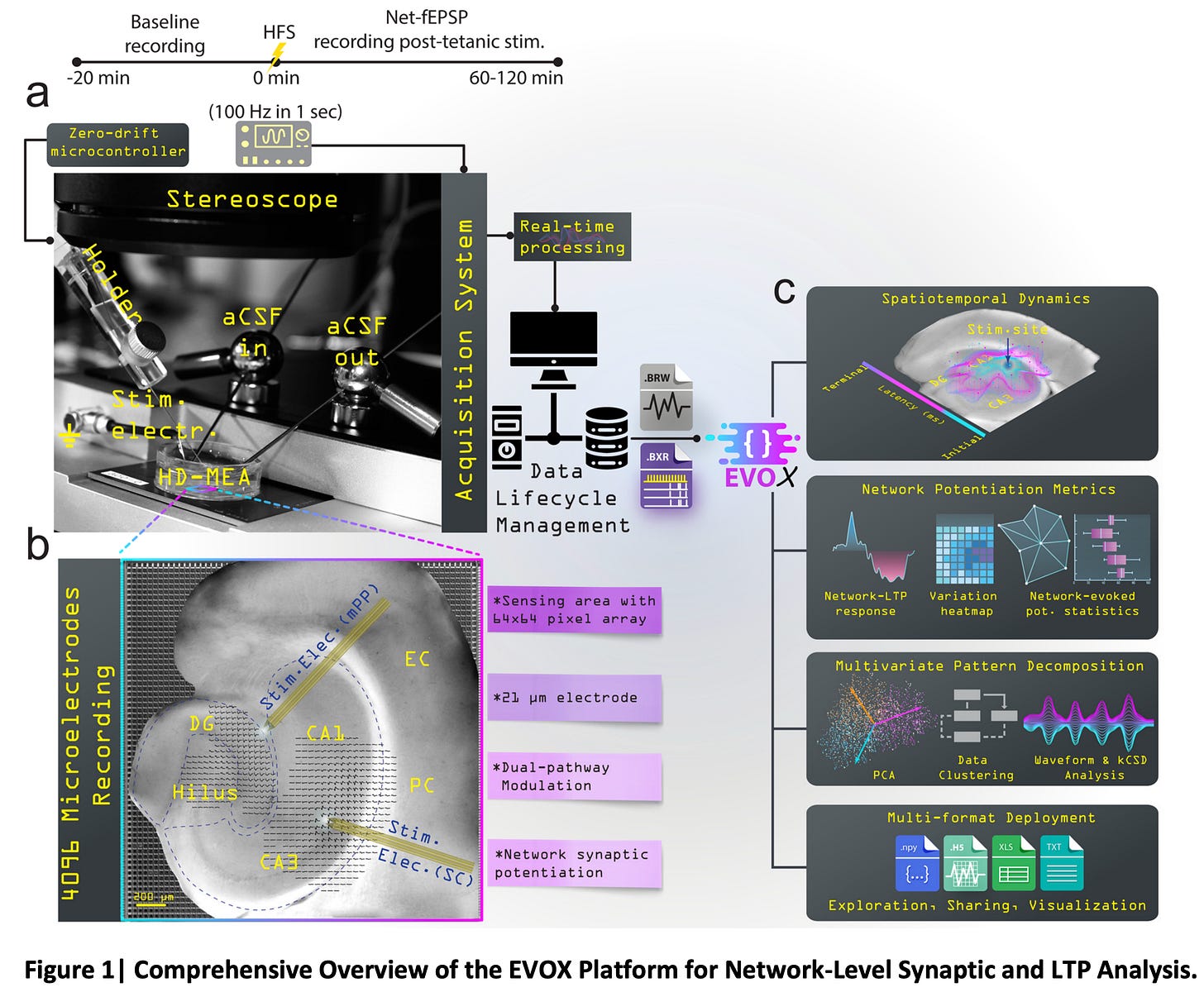

There are new forms of measuring LTP in brain slices that are more comprehensive. Perhaps if one of these were used, the results would be more convincing.

Electrical activity in whole brains

Back to Laura Deming discussing Cradle:

The milestone after that is to show that you can cryopreserve and rewarm a whole brain while maintaining long-range electrical connectivity between certain sets of neurons.

This reminds me of Isamu Suda's famous cryopreservation experiments from the 1960s and 70s. Suda and colleagues reported that they were able to cryopreserve cat brains at -20°C for weeks to years, and upon rewarming, detect coordinated electrical activity that resembled expected brain rhythms.

While these results were influential and widely discussed in the early days of cryonics, they have not been independently replicated since then. I previously predicted that Suda et al’s result would most likely replicate, conditional on it being tested:

But this wouldn’t really tell us whether long-term memories are still preserved. More generally, when using the isolated whole brain approach, it is not trivial to test whether long-term memory has been preserved or not. There would likely need to be a whole set of side experiments to show that the electrophysiological measurements present in the isolated brain preparation actually correspond to the preservation of one or more long-term memories. This seems pretty far away from a neuroscience perspective, leaving the cryobiology questions aside.

There would also be significant ethical questions involved in such experiments, because the isolated brain would need to be treated with the same care and respect as a living organism.

Reversible cryopreservation of whole mammals

The last milestone listed on Cradle’s roadmap is “Reversible whole-body cryopreservation of a small animal model.”

This is really the core of the problem. If you can do this, then you can directly test the degree of memory preservation in a straightforward way that doesn’t require any inference.

But it's also what most people are skeptical about. It requires figuring out not only how to reversibly cryopreserve the entire brain, but also all of the other tissue types and organs in the body. Today, we can't reversibly cryopreserve the vast majority of them. So I think this is not going to happen anytime soon.

Still, as the saying goes, if we knew what we were doing, we wouldn't call it research. I like the idea of getting a bunch of brilliant people, giving them adequate funding, and seeing if they can make some headway on this problem.

Personally, I'm more interested in structural brain preservation, which is mainly because I think it might already be sufficient to preserve long-term memories and other aspects of personal identity that people care about, so I want it to be available in a high-quality manner as soon as possible to as many people as possible. I'm always curious to learn more about why others seem to disagree with me about the potential in contemporary structural brain preservation.

But I would also love to see the reversible cryopreservation research hypothesis be tested better, and to see the field grow, so I wish everyone at Cradle total success. I fully agree with Laura Deming about the fundamental motivations for the field: it is not being pursued largely for social reasons, it could potentially save lives and let us spend more time with the people we love, and it could help us get to the stars.

Tomorrow Bio is innovative in a lot of other ways too, including their technical approaches. I don't want to make it seem like they only do public relations. But I think they are the first to intentionally spend significant resources on this, which is notable here.

On free cryopreservation: Some data on this: Charles Platt created a competition for Omni magazine. The prize was a free preservation. This didn't generate new membership. Much later, despite the winner not ever being in contact, he did actually get cryopreserved. (James Baglivo, if I recall.)

On your footnote about the current efforts by Tomorrow Biostasis: Agreed, they are putting a good effort into marketing and it will be interesting to see how it works out I dispute the statement that they are the first to spend significant resources on this, although it depends on how much you consider "significant" and over what time. For a couple of years when I was running Alcor, I worked with Media Architects to create a new website, create around 30 new educational videos, and other projects (including the idea for the display dewar which Alcor recently adopted).

Our budget never exceeded around $5,000 per month and was less than that for most of the time. Alcor grew during that time, unlike now. Unfortunately, the Board cut off funding for this work so we didn't get to build on it and see how effective it was. We wanted to expand further and more systematically into social media but didn't get the chance. (It may not be coincidental that the Alcor board had then and has now ZERO directors with a background in communications and marketing.)